818-424-2116

Michelle Dowd still remembers the phone number from her childhood. But rather than being tethered to a landline phone on the wall of a cozy home, Dowd’s number rang to the office of the Field, a religious cult in the Angeles National Forest, 15 miles and a universe away from downtown Los Angeles.

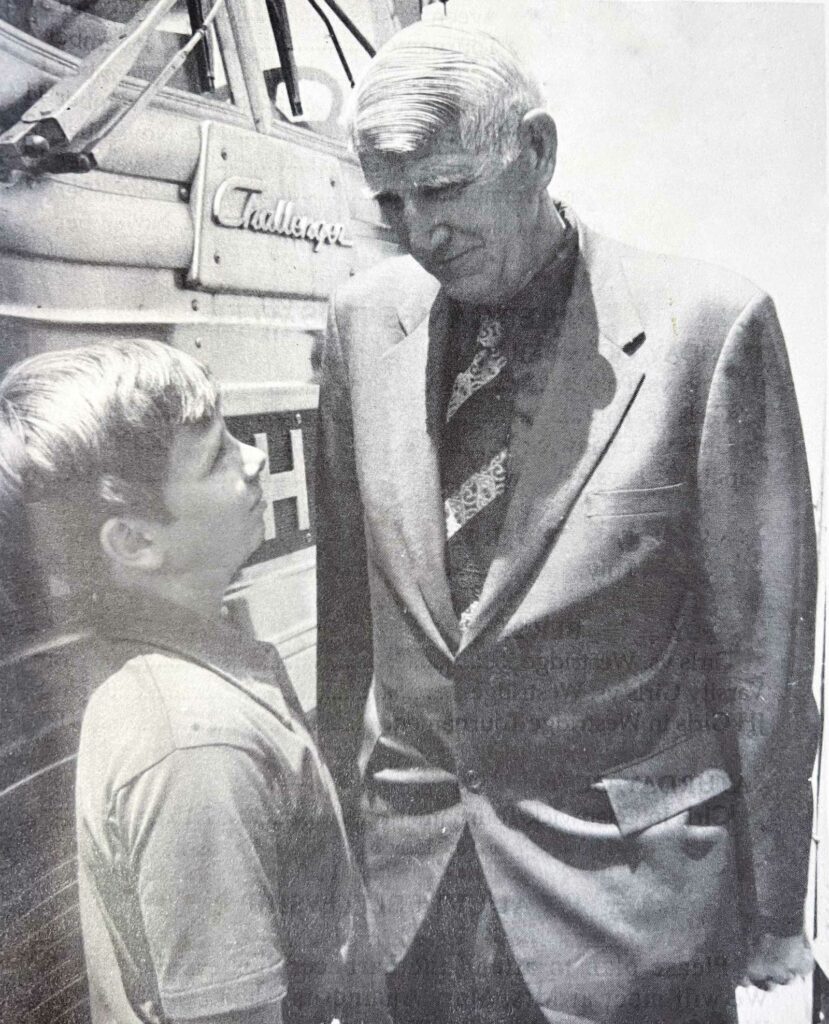

For 10 years, from the ages of seven to 17, Dowd lived in the mountain wilderness with the Field, which was founded in the 1930s by her grandfather, Orrick W. Hampton. It was an isolated operation that began as a boy’s camp, a pastiche of fundamental Christianity and the Boy Scouts. The Field’s 16 acres were leased for $100 a year from the feds. Weekend excursions for local boys took in the 700,000 acres of the forest. Eventually, it grew into a full-on enterprise, a village of charismatic leadership, subordination and the strictest, even fanciful, interpretation of Scripture.

Dowd tells the story of her life in the Field in a brow-furrowing autobiography, “Forager: Notes for Surviving a Family Cult: A Memoir,” which came out in hardcover in 2023 followed by the paperback in February.

It chronicles her journey from the cult to the halls of academe, where she earned a master’s degree in English language and literature/letters at the University of Colorado Boulder. She spent 25 years as an English and journalism professor at Chaffey College in California’s Inland Valley. “Forager” is her first book and its success has afforded her to this year leave her day job at Chaffey.

So when you saw her on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in April, smoking a Foundation cigar like a champ, it was a smoke of victory for Dowd. She is now a full-time author.

Cigars for Dowd began with a simple offer; she was at an outdoor music event at a venue that featured a small humidor. A fellow patron asked if she would like to try a cigar and she accepted.

“This was my first cigar and I loved it from the very first taste,” Dowd says.

The occasion was one of many enlightenments as Dowd has grown from adolescence in a group that espoused celibacy, plenty of tithing and the now-obligatory looming apocalypse. The end date of 1977 came and went. Followers were told that Hampton would live to be 500 years old – he died in 1982 at 75 – and that they would be among those who ascend to heaven when it all goes down. Another dubious promise.

“They told us the dates were off,” Dowd says.

She was born to parents in the Field in Pasadena, California, three girls, one boy, to a military vet dad and ambitious autodidact of a mom in El Monte, California. They were not setting the world on fire: “I grew up there living next to a dump,” Dowd says. She attended public schools until the decision was made to help turn the Field – a de facto family business – into something “special,” and Dowd’s indoctrination began.

“We were all pulled out of our public school and lived on the mountain,” Dowd says.

As she grew from a kid into a teenager, Dowd had little exposure to popular culture, with her sole connection to the outside world a Sears catalog squirreled away under her mattress. Dowd was not allowed to fraternize with boys, and sometimes existed, like her peers, on plants and berries. She was forced to wear a non-body fitting robe, called a djellaba – “so we don’t tempt the boys” – and to downplay her femininity. Sex was forbidden unless married and then only for procreation. Dowd, as well as all the members, were told that comfort and care were sins. As a part of the original family that began the Field, she was treated more strictly than the others.

In other words, Michelle Dowd was raised by wolves.

Cigar Snob: What counts as a cult? There are thousands of cults that are operating right now, right?

Michelle Dowd: There are an estimated 10,000 cults operating right now, but most of them fold within 10 years, almost always over power struggles. The ones we hear about are the ones that go up in flames, like Waco or Jonestown. Those are known because of the horrible tragedies. They have a charismatic leader with a mercurial temperament, who decides who stays and who goes. They have the ability to control people. Kids are pretty easy to control but there are plenty of adults that are as well. It’s easy to control people through a combination of charisma and cruelty. I was told not long ago that the Field was a successful cult. And I didn’t even like that word. I wouldn’t use it. But I know that I never thought I was from a cult when I was young. You know it’s much harder to do that now, with social media. We didn’t have access to information, but now, you can see that things are different in other places.

CS: This group, the Field, said the world would end at some point soon, which kind of kicked off the survival training. What did it mean to do survival training in a religious cult fashion?

Dowd: Presumably, we weren’t going to survive the apocalypse, that’s what my grandfather said. But 1977 came and went, then my grandfather died [in 1982]. And then my mom kind of took over this training. My mom was big on, you can’t have a jacket, you can’t have a flashlight, you can’t have matches, you can’t have anything, and you have to be able to survive. The idea of survival is different from preppers, who are always prepared, right? Survivalists believe that you are going to be nomadic. And so your goal is just to live with nothing. And so when people talk about the end of the world, things like cockroaches survive. You have to be the cockroach; you have to be something that can survive on nothing. You have to know how to find the minimum needs. Our version was that some of the people would go up to heaven at the Second Coming, or the apocalypse, there would be a trumpet with sounds, for example. And then whatever caused a nuclear war, whatever ended up being the destruction that God would put on the earth, there were some people who would rise to heaven prior to that, and then there’d be some people left behind. My grandfather believed that he was a close relative of the Son of God, or at least a prophet. And I was blood family. He believed that his family then would be like Noah who built the ark, or Jonah, who was wild in the belly of the whale, like we are the people who God chose to bring centers into the light. So we, our family, would be left to find the people who needed help. A lot of the people from the Field would go up to heaven. We don’t know who, but I probably would have been left behind. My mother trained our family and the people who came to the mountain to do this training but more casually. Not as intense as our family.

CS: How long would you go out for this?

Dowd: It depended. I would be out a week but the other people mostly stayed out only for three days.

CS: So you can survive in the wilderness of the California mountains. What do you do if you’re out hunting or fishing and all of a sudden, you’re lost?

Dowd: The first thing you do is stay put as soon you recognize you don’t know where you are. Stop moving and sit down. The first thing to do is to get yourself calm. Because the natural thing is fight or flight. And if you’re in fight or flight mode, you are not going to think clearly. Honestly, if you can do that, you’ve got a fighting chance. My mom gave us this phrase, ‘Survive with Fear, Survive with Faith.’ You can believe in God. That’s fine. But the faith is also in yourself. There’s the acronym, so the first one is shelter. You need shelter even if you think you don’t, because you either need shelter for the sun or you need shelter from the cold. Many people die the first night they are lost because they didn’t shelter. You have to decide where to build, if you’re lucky, there will be water and you can build near that. Be careful not to build near an animal trail, which a lot of the time is clear. If you get in their way, mountain lions or bears, they will attack. But you want to make sure you have a place that is covered and try to keep warm.

CS: If it’s 50 degrees would someone die of exposure?

Dowd: You’re better off if it’s cold rather than hot. And the second of that acronym is fire. If you’re somewhere warm, that’s fine, but in the majority of places, you will need a fire at some point. Next is signaling. Find any item of clothing you have that is colorful. Assuming you’re not injured, find the highest point and put that colorful item on a stick and put that at the highest point. If you have a mirror, you can use that as well, but even white clothing is a powerful color.

You signal at whatever flies over. If anyone knows where you are, there is going to be a search and rescue mission and a helicopter that may come by. Because if anyone is searching from the ground, it’s really hard to find someone who is lost on the ground. You do the signaling before you do water or food. And remember, you’ve only got three days of a search and rescue before they give up and presume you’re dead. The last of the acronym is food, or really water.

CS: You talk in the book about eating all kinds of things, and each chapter begins with some kind of plant that can be eaten in survival instances, like pine cones, weeds and various other foliage. One thing that isn’t mentioned is how this stuff tastes.

Dowd: It’s not delicious. It’s nothing like the grocery store. Very rarely do you taste anything out there that tastes good. What you learn is what has the highest calories. And then what is dangerous? What has the most nutrition? What do you need to balance a diet? But I wasn’t going around going like, ‘Oh, these rose hips, these are almost like cherries.’ They’re not. Nothing in nature is as sweet as what we have cultivated as humans. As humans, we have spent years making things that are palatable for us. Nature doesn’t really give them to us quite that way.

Photo credit: Michelle Dowd

Photo credit: Michelle Dowd

Photo credit: Michelle Dowd

CS: So living off the land tastes like crap.

Dowd: Yes, pretty much. When people say they are living off the land, they mean agriculture. Mostly they’re having gardens. We ate bugs. A lot. I mean, not in everyday life, but when you’re foraging and practicing survival, you have to. It’s a reliable source of protein. Ants.

CS: Seems it would take a lot of ants to fill you up.

Dowd: Well, it does. Larvae, though, are something that has a lot of protein and is larger. Elderberries are super nutritious, but you have to boil them in order to take out toxins. There’s a lot of plants that you boil because otherwise they’ll upset your stomach. Chris McCandless, who Jon Krakauer wrote about in Into the Wild, died from eating something he shouldn’t have.

CS: You speak in the book of the Trip, or this journey where people in your group would load up and go across the country and talk to people about faith. It was kind of a tent revival show that we still see in parts of America today.

Dowd: My dad started driving the bus for the Trip when he was 18, in the 50s. I believe that’s when the Trip started.

CS: So this was like the Partridge Family or something? Everyone in this bus touring?

Dowd: It’s bigger than the Partridge Family.

CS: What was the format of these trips?

Dowd: My sister and I went on a Trip when I was just a few months old. Obviously, I don’t remember it but my sister told me we were in a different campground every night. The guys’ trip was 10 weeks long every summer, staying in tents. Then around 1974, they started doing girls’ trips, those were eight weeks long. Because we were part of the family, we went on boys’ trips too. The boys were usually ages 14 to 25, their families had let them go to be in the Field. I didn’t like that when I was little because they would leave us in the tent while they went out to speak and talk with people. We just had to sit there all day.

CS: Do you remember the geography and any history you learned from the trip?

Dowd: Yes, we went to Appomattox, a lot of the Civil War sites, a lot of the battlefields. We went to Gettysburg, we learned battle formations. I remember seeing the Passion Play at a place in the Ozarks, it was in a forest, it takes place in the rocks up in the hills, right? In retrospect, I’d say I saw most of the country, the contiguous United States, that way. We went from the West Coast to the East Coast, then down to Florida. We went into Canada; we took long trips to Mexico.

On the trips, it wasn’t vacation. We were panhandling, asking for donations, putting on plays for people with very elaborate sets. Everyone was separated from their parents for this, it was like religious training. We ran every morning, two miles, before you did anything, even use the bathroom or eat. Then we’d have to wash the vehicles, some kind of chore.

CS: What kind of lessons did you take away that might be handy now?

Dowd: I feel like as a kid it was very troubling to me, but also it was very valuable. People think that air conditioning is necessary, for example. Someone will say you can’t sleep without air conditioning, and that is ridiculous. As I grew up and came in contact with other people, outside, I’d hear them say things like that. I’d also hear people talking about black churches and going to black churches. We had black people in our community, but we did not call them one thing or the other, African American. We did not identify race or ethnicity. I would now say I had Black brothers and people who will say, ‘you were my sister.’ It never occurred to me they were Black, because all that mattered was that you were unified in Christ and that you were in this group. I was talking to a [Black] man who’s a little older than me, but he was raised as a brother to me. And I said, ‘Did you see your skin color? Did you feel different?’ And he said, ‘Not until I left. I honestly never knew.’

CS: Your path to getting away from the cult was when you developed an autoimmune disease and were hospitalized. That’s a rough way out.

Dowd: It gave me information. But I was in the hospital. At that point, I was aware that there were families, kinder than my family, more loving, and I didn’t have the awareness to want that for myself in an active way. Like I couldn’t say that out loud. But if I hadn’t gotten sick, I’m not sure I would have been the very first child born in the Field to ever get out of that organization. I was the first person to leave who was born there.

CS: There were TVs in the hospital. That’s a scary start, but it’s a start.

Dowd: The first show I saw was Bonanza. I also liked Big Valley. This was the 1979 to 1982 period. There were only certain channels available, it was a children’s hospital.

CS: Once you got out of the hospital, through contacts you made there, you began cleaning houses for people. And that led to you leaving the Field. A woman you were working for connected you to a way to go to college, which ended up happening.

Dowd: I never made a decision to leave, per se. It was a set of circumstances that led to the inevitability that I could not stay. It was very impulsive. I never let myself think I was leaving. But I did.

CS: Did you have money?

Dowd: I had a little from house cleaning but I got a full ride scholarship for college. I had a concept of money, and I knew I didn’t have it. I didn’t have a bank account. When I got to college, I knew there were kids with money because they had things and they could buy things. I just wanted food and shelter.

CS: So you lived in a dorm in college. Did you have any Mork moments? That is, the alien character in the show “Mork and Mindy” who comes to Earth to study human behavior.

Dowd: Every moment was a Mork moment, and I had no idea of who that was at the time. I didn’t make any friends because I had no idea how to. I didn’t know it, but I was very attractive and I got a lot of attention. I lived in a coed dorm. My roommate was a super conservative Mormon. She didn’t drink coffee. She didn’t drink alcohol. So we were two very conservative girls in our space.

CS: So boys must have been an interesting thing to navigate.

Dowd: I went to the freshman dance before classes even started. And this basketball player who was living diagonally from us across the hall, gorgeous guy who had all the girls he wanted. I knew they all liked him, but, like, whatever. He asked me to go to this dance. I went to the dance. He kind of took my hand and like, kind of tried to hold me on the dance floor for a few seconds. I was so freaked out I ran away. Hooking up was such a foreign concept for me. Like, I couldn’t even imagine that. I had never had a social relationship. I never did in college, really. I had never had the experience of having a friend yet, even through college. I mean, other than the friends I was born with.

CS: To really understand your journey, your book is the place to be. You went on to be married to someone who had also been in the Field, have babies, get some higher ed degrees and become an educator. The book, though, is this crowning jewel. So let’s talk about cigars.

Dowd: I started smoking cigars about 12 years ago at an outdoor jazz place that had a humidor, wine. Someone asked me, and I accepted. It felt so freeing. I loved the way it enhanced conversation. So I started going there, then after yoga, I started going to a cigar lounge in Upland, the Cigar Exchange International. There’s an indoor and outdoor and they would have live music every weekend. Beer, wine, all sorts of whiskies. I felt that smoking a cigar made me feel good and there were no consequences. It’s not like overeating or overdrinking where you feel bad afterward.

CS: What do you drink with a cigar?

Dowd: My younger sister gave me my first alcohol, when I was in my 30s. It was after I’d had all my children – I didn’t drink when I was raising children – and we were at her house, and she blended margaritas. But I can’t say that gave me as much pleasure as my first cigar. I kept smoking, one of the deans at my college liked to smoke cigars, so he would come over during Covid and smoke in my backyard. I smoke about once a month.

CS: Maybe most famously on the Joe Rogan show.

Dowd: When I went on Rogan, I knew that he smoked cigars, and I thought he must have good cigars. And I thought, ‘why not do something that he already likes to do?’ So when I got to his studio, he asked if I wanted anything, drink, cigar. And I said ‘cigar.’

CS: You got to smoke the Rogan blend that comes from our pal Nick at Foundation.

Dowd: Yes, and afterward, Nick sent me some cigars and some other stuff, swag. He sent me some Upsetters, some Tabernacles.

CS: So now you’re ready to do the next book.

Dowd: The proposal is done. It will be an extension [of Forager], working title “Prodigal Daughter,” kind of picking up where we left off. It flashes back to some of the first book, but it starts when I’m 29. I skipped a little over 10 years, because I feel like it’s very important in memoir writing to tell a story not to just give facts about your life. It does give you a reference point to what happened when I left.

Dowd’s harrowing saga has a happy twist. Dowd has four flourishing, grown children and four dogs, and lives in a 1920s home on an acre in California’s Inland Valley. Her literary career is on fire, as is a possible film concept, for which she was commissioned to write the first draft. Dowd hosts a yoga and beer night at a local brewery, Yoga on Tap at Claremont Craft Ales, has friends over to her home, teaches writing workshops, and works on her Substack. She frequently backpacks in the mountains. Only this time, it’s her choice.